NYC Congestion Pricing: Three Months In

Early results from the Central Business District Tolling Program are promising, but the program is more at risk than ever before.

If you’re like me, then you’ve been overwhelmed by a deluge of bad news lately. Thankfully, preliminary yet positive results from New York City’s congestion pricing program have offered a small but much needed respite.

Source: NBC 4 New York

The Central Business District Tolling Program was passed as part of the budget for the state of New York in 2019 and officially began its first phase on January 5th, 2025. The law levies a toll on vehicles that pass through Manhattan south of 60th street off the West Side Highway and FDR drive, an effort to reduce traffic congestion and encourage people to use public transportation. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is expecting to fund $15 billion in capital improvements through municipal bonds backed by tolls, with the law specifying that 80% of funding will go toward the subway and bus system. In the first month alone, the city collected nearly $50 million in tolls, and is projected to collect $500 million in year one.

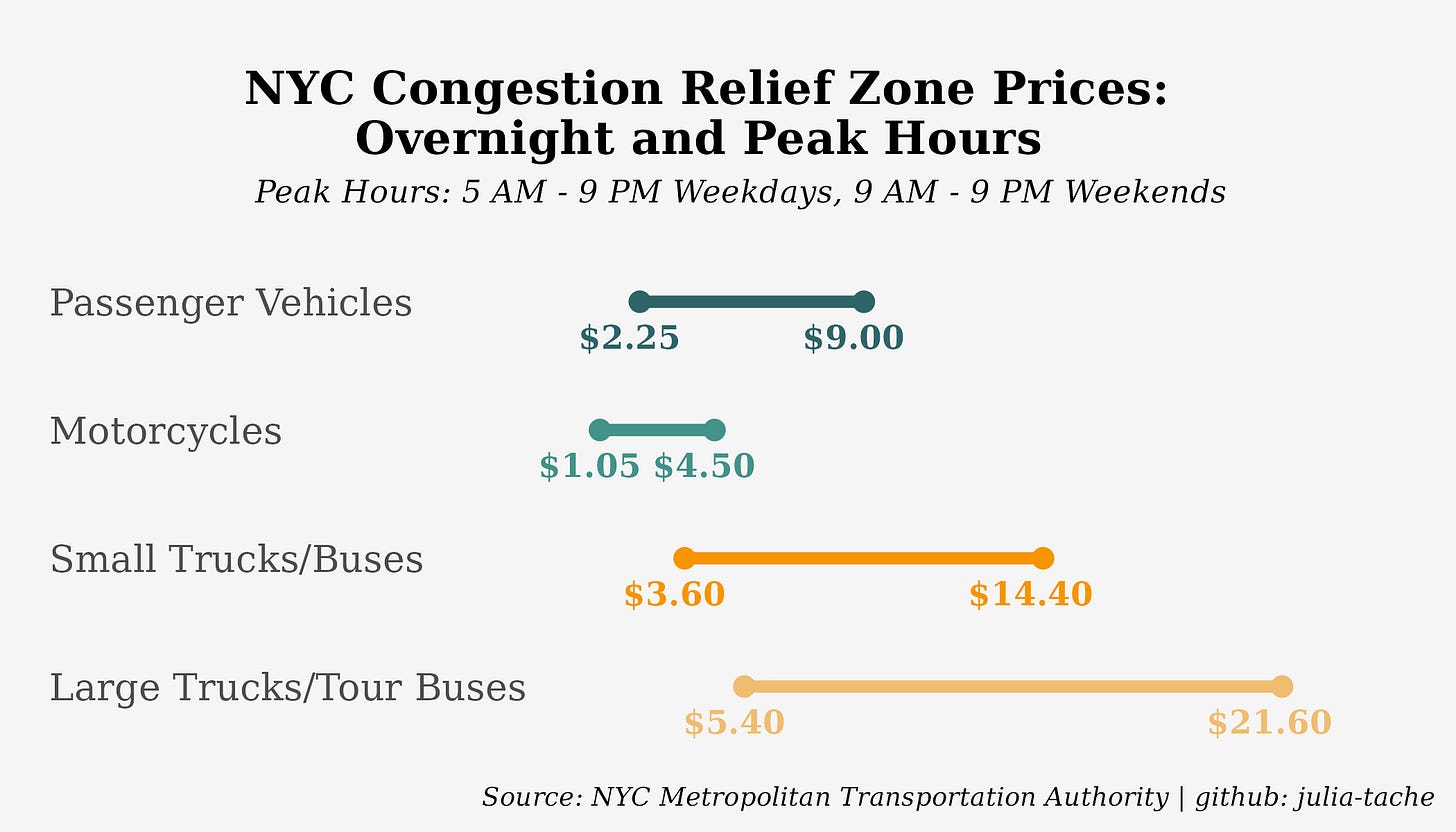

The program is structured by charging drivers entering the central business district, otherwise known as the “Congestion Relief Zone” (CRZ), based on vehicle type and hour of entry. At peak hours, which are between 5:00 AM and 9:00 PM on weekdays and 9:00 AM and 9:00 PM on weekends, car and small commercial vehicle drivers pay $9.00, motorcyclists pay $4.50, small truck and non-commuter bus drivers pay $14.40, and large truck and tour bus drivers pay $21.60. Incremental increases in the toll will take place over the course of several years.

For all other times, drivers are charged lower, “overnight” prices. Passenger and motorcycle re-entries and certain vehicles are exempt from the toll, and drivers coming in from certain bridges and tunnels are provided a credit toward the CRZ charge. Taxis and ride-hailing vehicles are tolled slightly differently: every trip to, from, or within the CRZ costs between $0.75 and $1.50. 22% of revenue came from taxis and vehicles-for-hire in January while most income came from passenger cars.

Though the program has been in place for only a quarter of a year, there have already been improvements in commute times and noticeable increases in public transit ridership. Over time, less traffic, higher rates of transit usage, and enhancements to existing transit fleets will reduce pollution and improve air quality. These early but promising results suggest that the congestion pricing program is on track to being a model for other cities to adopt across the U.S.

Entries and Driver Behavior

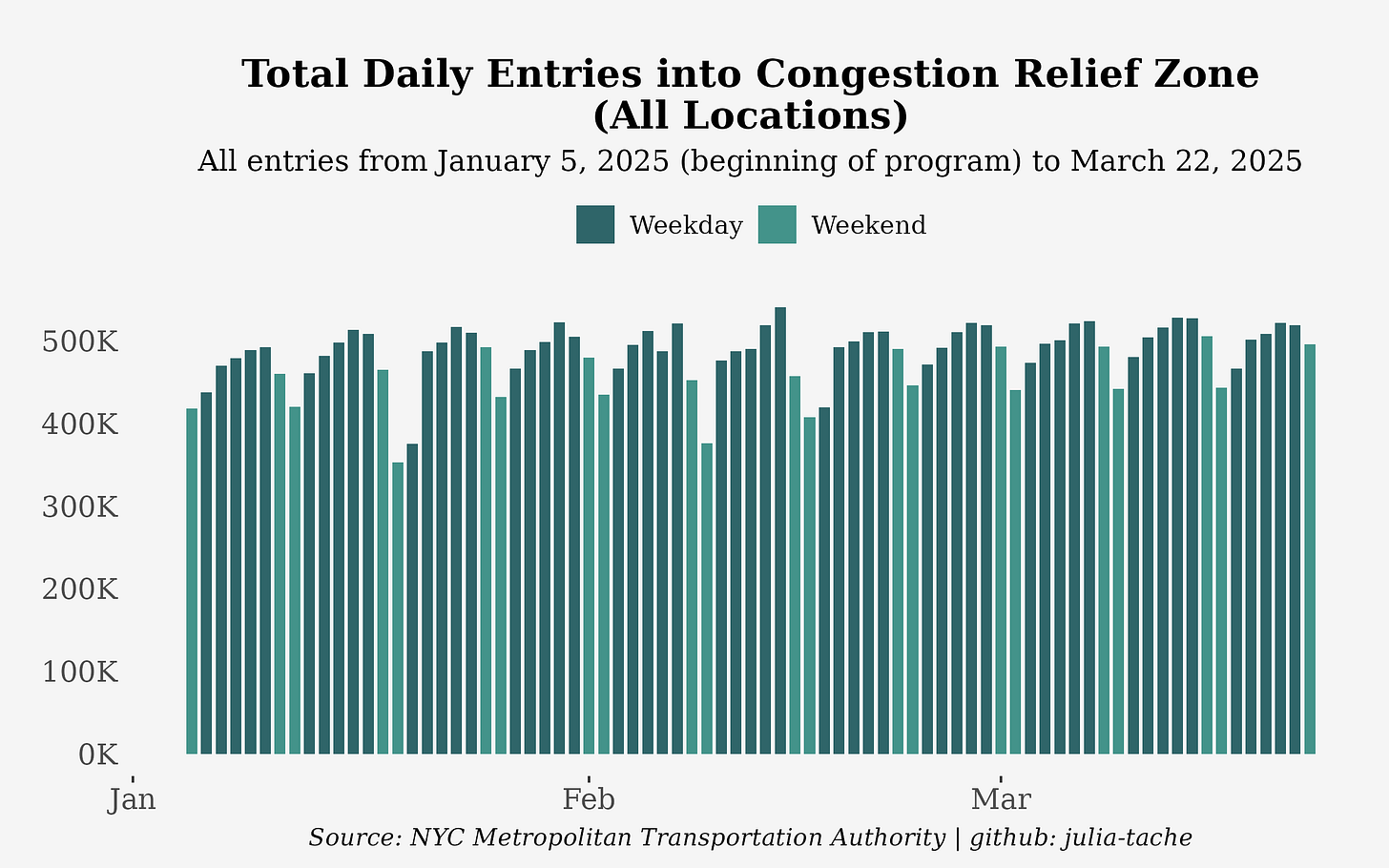

Early estimates showed that travel times in the CRZ have shrunk since congestion pricing was implemented. According to the MTA’s available data, total CRZ entries have only slightly increased over the last three months (the most current data available goes up to March 22nd). The average number of weekday entries into the CRZ from January 5th to January 31st was around 471,934. This is down by 19.1% from the MTA’s conservative January baseline of 583,000 vehicles per day. Passenger vehicles, which make up the largest share of CRZ entries, made an average of 278,220 crossings per weekday over the last three months. With the vast majority of tolls collected electronically via E-ZPass, the risk of widespread fare evasion is relatively low

.

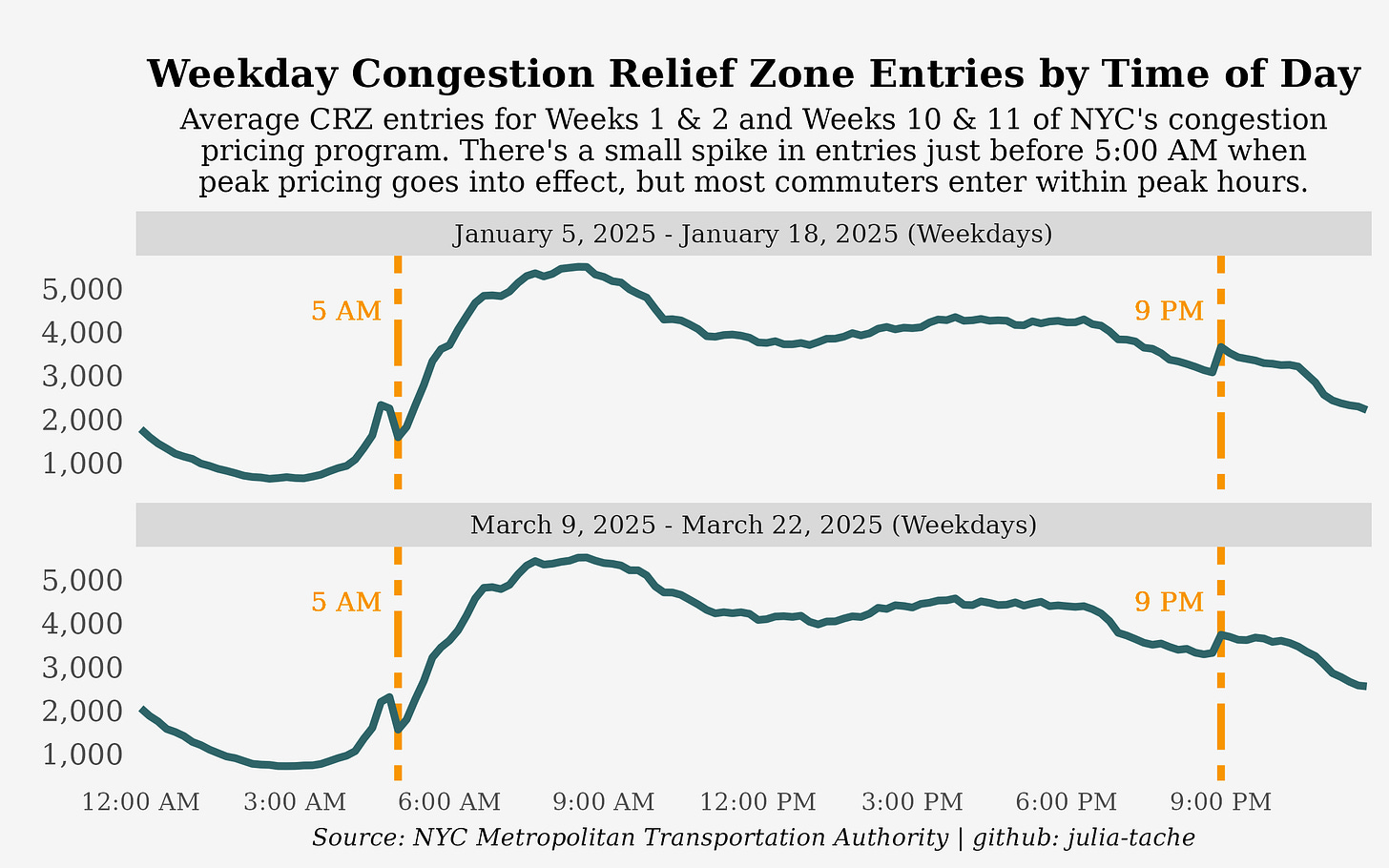

There is some evidence that certain commuters and commercial drivers are purposefully entering the CRZ just before and after peak pricing goes into effect at 5:00 AM and 9:00 PM on weekdays, as shown in the graph above. However, most drivers enter within peak hours, and there does not seem to be any indication that more drivers have been trying to enter the zone earlier over time. 95% of revenue is collected during peak hours.

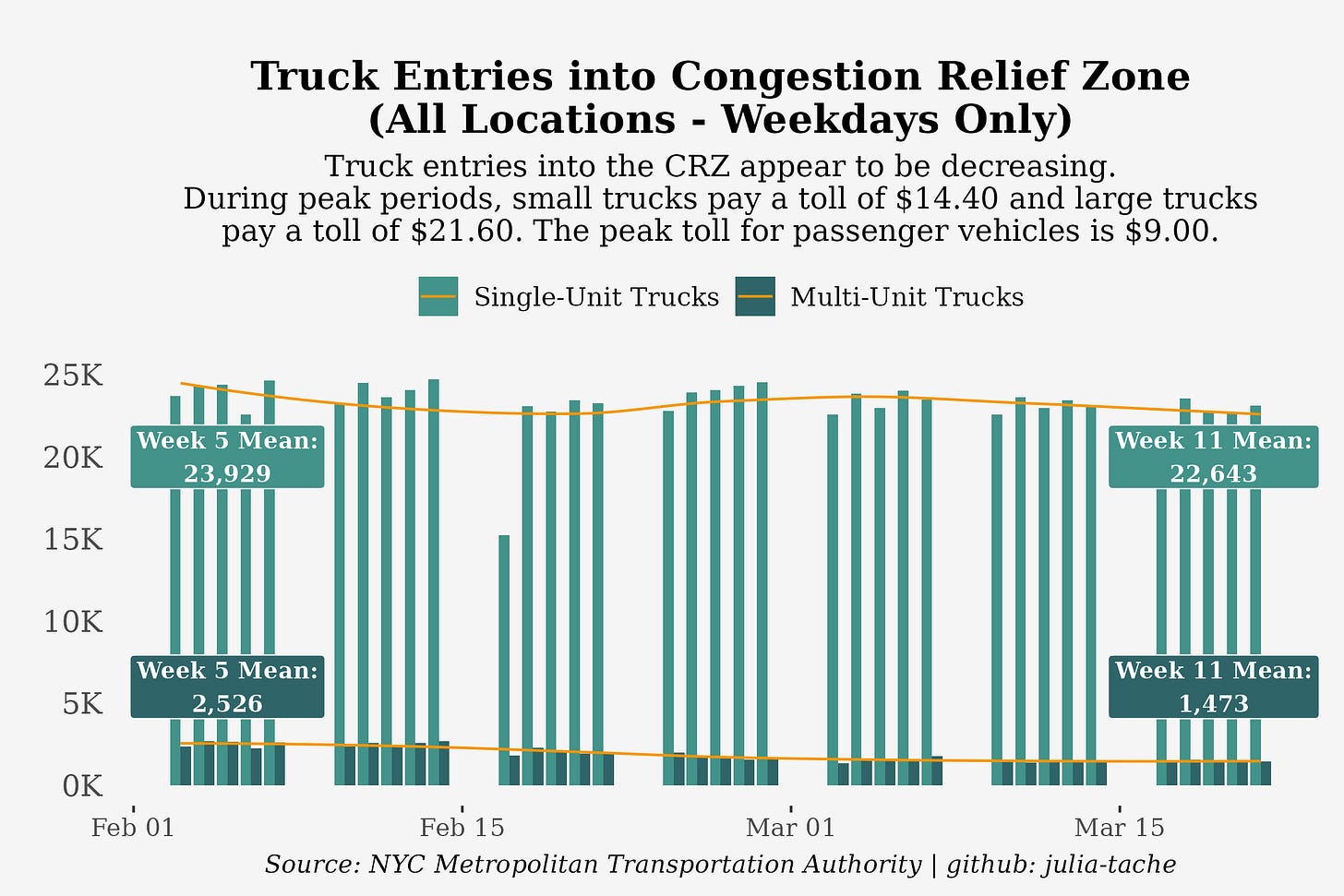

While aggregate vehicle entries have remained relatively consistent over the last few months, certain kinds of vehicles have been entering the zone less over time. There was a reduction of entries on weekdays of small trucks by 5.4% and of large, multi-unit trucks by 41.7% from week 5 to week 11 of the program. Distribution-focused companies may be adjusting to pricing by opting for smaller vehicles for “last mile” deliveries and optimizing routes to avoid higher fees. There could be other factors at play, such as reduced demand for consumer goods amid an uneasy economic outlook. While the effects of reductions in truck volume can only be speculated at this point, less large vehicles on the road could be contributing to the reduction in traffic times.

Meanwhile, motorcycle entries have increased. As shown on MTA’s very useful dashboard, the weekday averages for motorcyclists have increased from about 1,490 (from January 6 to January 10) to 1,882 (from March 17 to March 21), or 26.3%. Delivery companies and fiscally-minded motorists taking advantage of warmer weather may be opting to use bikes more frequently. Taxis and rideshares had a weekday average increase of 12.9% from the first week of the program compared to the week of March 17th, and have also increased in presence on weekends. On Saturday, March 15th, there were almost 200,000 taxis and rideshare crossings, the highest level that week.

Traffic Report: A (1010) WIN(S)

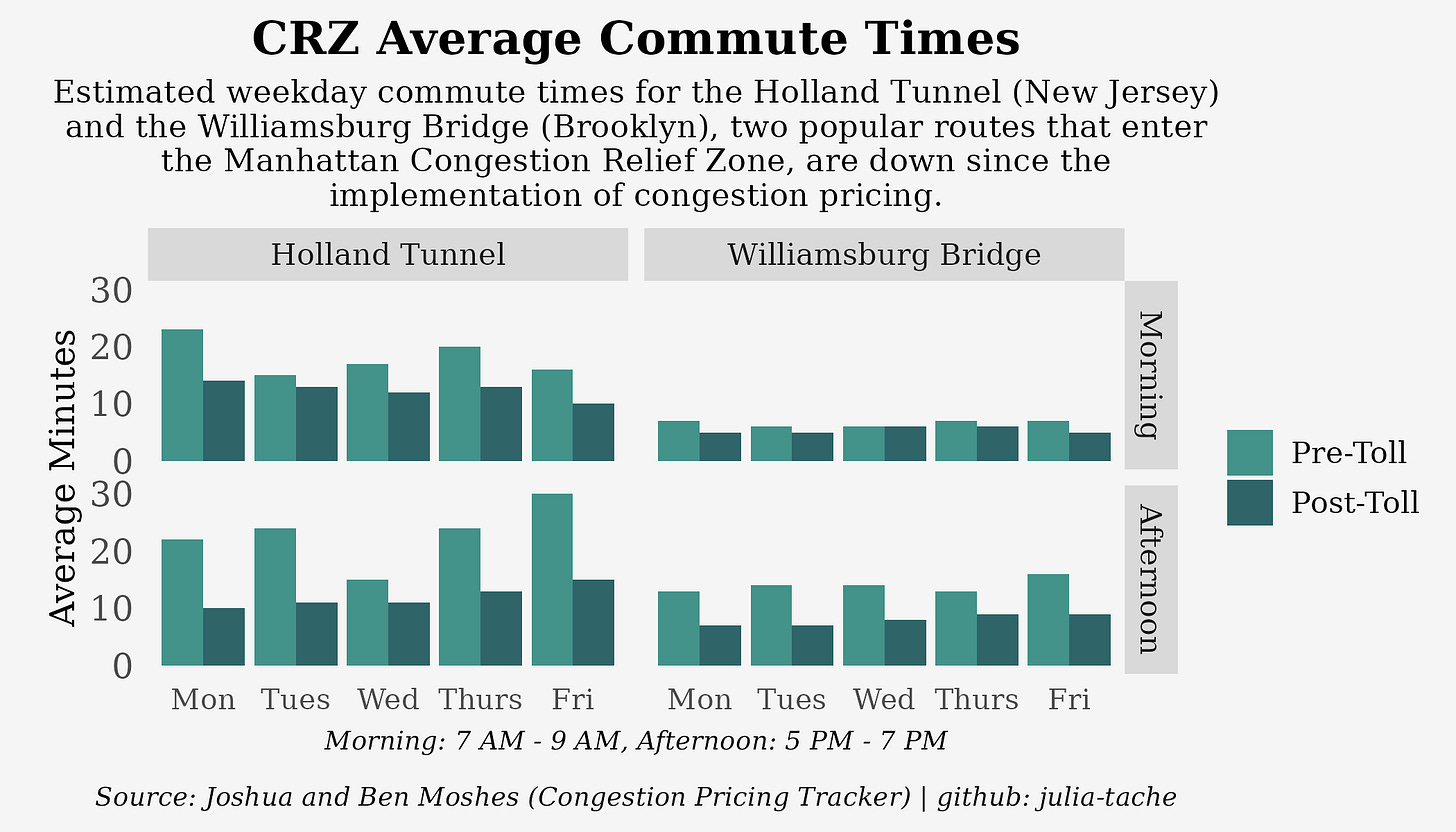

With fewer vehicles on the road in general, in particular large capacity vehicles, traffic times appear to be getting better across the zone. Several bridges and tunnels cross over into the CRZ from New Jersey and the outer boroughs. The Congestion Price Tracker provides real-time estimates of commute times based on Google Maps data as well as average times pre- and post-congestion pricing. Two popular routes used to enter the CRZ from New Jersey and Brooklyn, the Holland Tunnel and the Williamsburg Bridge, have seen some significant traffic relief on weekday mornings and afternoons.

Average commute times on the Holland Tunnel on Monday mornings and Friday afternoons (calculated by averaging commute times between 7:00 AM and 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM and 7:00 PM) were especially high pre-toll: 23 minutes and 30 minutes. After congestion pricing went into effect, those times have now been cut to 14 minutes and 15 minutes. Afternoon commute times on the Williamsburg Bridge have been slashed by almost half on all days.

The largest share of entries into the CRZ come from north of 60th street (43%). According to the MTA, crosstown and north-south traffic times decreased by 20-30% and up to 20% in the first month.

Although there have been concerns that CRZ tolls would simply divert traffic to other areas, there does not seem to be much evidence that this has been happening at a significant level. The creators of the Congestion Price Tracker have noted that there were only slight increases in traffic on spillover routes after the first month. Crossings on the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, which goes from Staten Island to Brooklyn, were roughly the same in January of 2025 as they were in January of 2024 and decreased in February year-over-year. Only eastbound traffic on the George Washington Bridge is published, but the data show that monthly vehicle crossings in January of 2025 also decreased from January of 2024.

“The next stop is…”

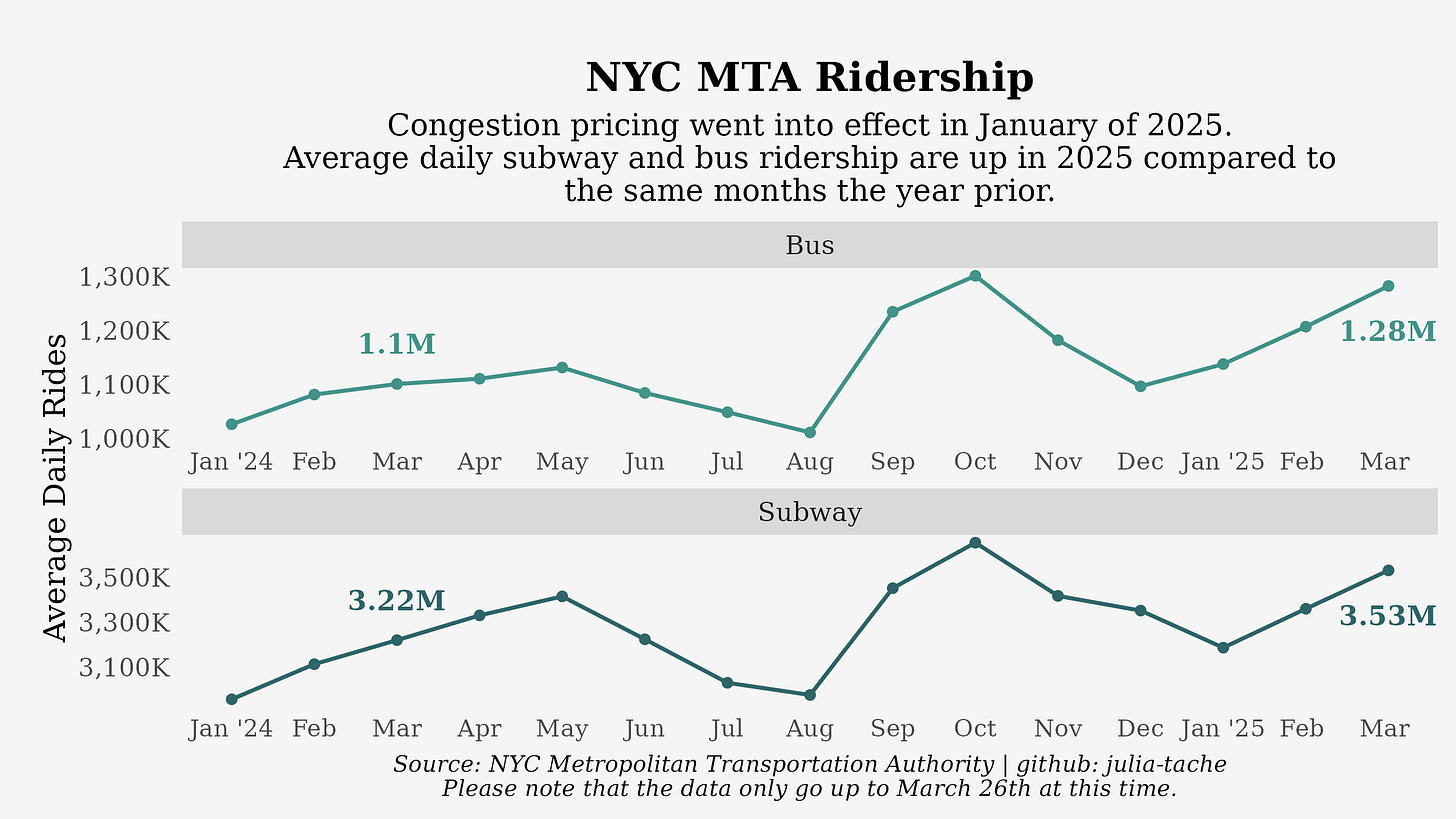

So where are all the commuters? The establishment of congestion pricing seems to have motivated more people to take public transportation. Subway and bus fares were increased in August 2023 from $2.75 to $2.90, which is still over three times lower than the toll for passenger vehicles in the CRZ. Subway ridership has risen from an average daily ridership of 3.2 million in January of 2025 to 3.5 million in March, while bus ridership has increased from an average daily amount of 1.1 million to 1.3 million.

When compared to March of 2024, the number of average daily subway and bus rides rose by 9.6% and 16.5%. Percent changes in transit ridership are higher over the last three months compared to the same time last year than they were in the previous three month period. In January, farebox revenues were 2.6% higher than expected.

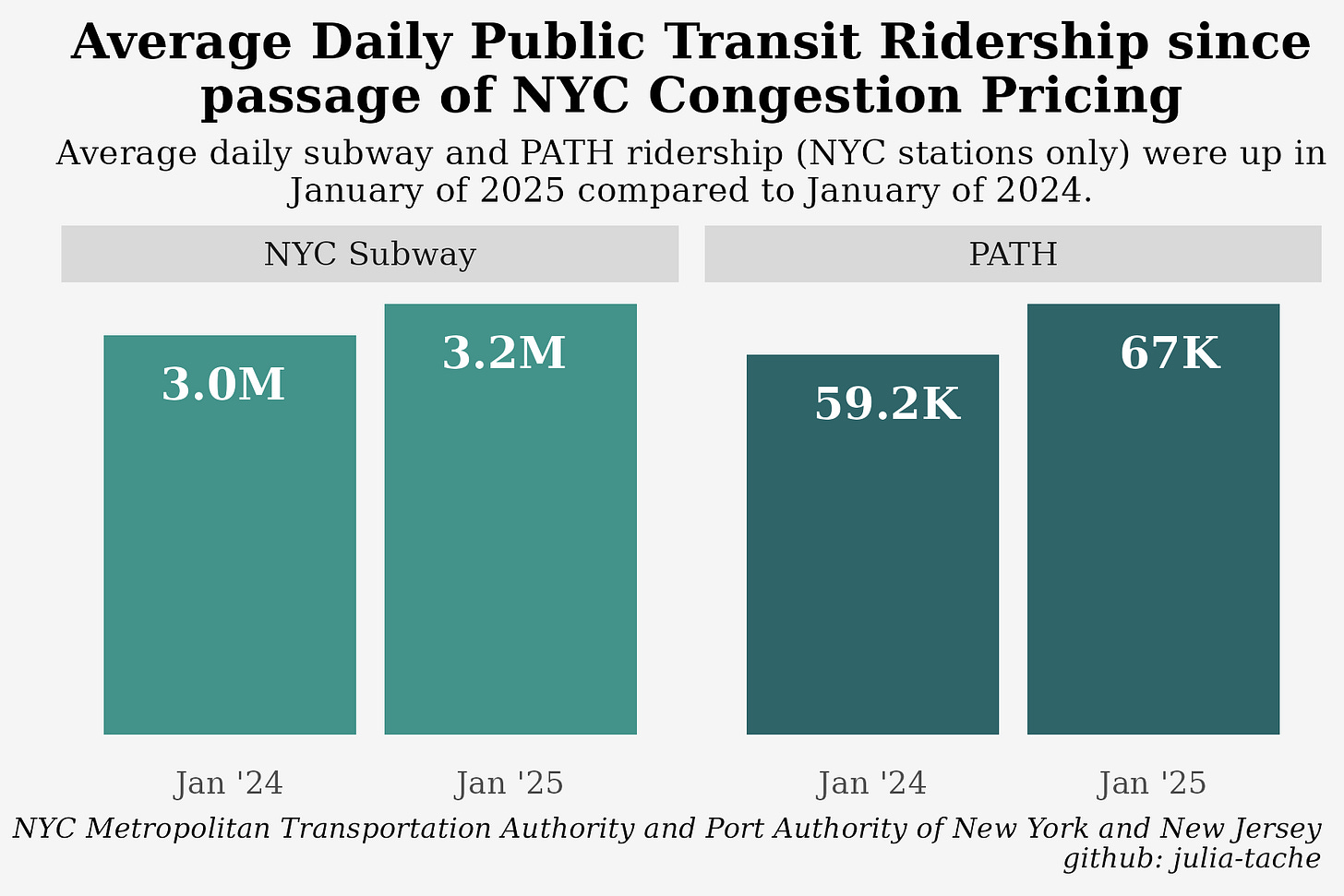

Other transit lines are also seeing increased uptake. The PATH train, which travels from Essex and Hudson Counties in New Jersey to midtown and downtown Manhattan (and a transit system I am very fond of), saw a 13.3% increase in January riders in 2025 at New York City stations from the year prior.

Public transportation usage in New York is unfortunately not yet reaching pre-pandemic levels where a typical weekday saw upwards of 5 million people per day. With many workers returning to the office either part- or full-time over the last year however, transit systems across the country are seeing growth in ridership. Higher demand for convenient transit may be helping put in motion much needed improvements in infrastructure and service.

The capital investments the MTA plans to undertake with new funding include updating subway and Long Island Rail Road station accessibility, deploying electric buses, replacing old subway cars, and extending the Second Avenue Subway upward into East Harlem. Additionally, the funding is expected to support the creation of 23,000 jobs.

You down with CRZ?

Despite early successes, congestion pricing in New York City has always been hotly debated, and is more at risk than ever. Several legal challenges, including one brought by the State of New Jersey, assert that the program is an undue financial burden on drivers and will harm small businesses, even though there is now more foot traffic in highly commercial areas. Some claim that current assessments of potential negative environmental externalities are insufficient, despite the MTA’s detailed, hundreds-of-pages long environmental impact report. In 2024, Governor Kathy Hochul nearly walked back on the plan, delaying the start of the program by six months. The original toll of $15.00 for passenger vehicles was eventually brought down by Hochul, reducing potential revenue gains.

More urgently, the Trump administration has had its eyes set on ending the tolls from day one. While congestion pricing was temporarily saved from termination on March 21st, the city was given only thirty more days to defend the program. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy lambasted Hochul and congestion pricing, calling the program an “unlawful pricing scheme,” and has threatened to withdraw federal funding from the MTA. The agency still needs to identify funding for half of its proposed $68 billion five-year capital plan, and the end of congestion pricing (which was allocated to support the previous capital plan) and possible cuts in federal spending would drastically put the agency behind on filling this gap.

The benefits of this program are materializing before our very eyes, including those related to quality of life. Early statistics showed that there have been less accidents and reduced honking complaints. Less cars mean that sidewalks and bike lanes are safer. Buses carrying several commuters and emergency vehicles can move through the streets faster. Fewer traffic jams mean people can get to where they need to go with less agita. Workers can spend less time gridlocked and more time at home.

The program also reveals how multi-faceted and coordinated our response to climate change must be. While the MTA has put in place environmental enhancement efforts in overburdened areas like the South Bronx, concerns about diverted commercial traffic are valid, and speak to the need for a policy response to encourage logistic fleet electrification. And there are other steps that could be taken to allow more people to take advantage of public transportation– expanding affordable housing in and around the city would allow more people to live near the economic hub of the area instead of driving in.

The Road Ahead

Mitigating and eventually reversing the effects of climate change will not happen overnight, but the fact that congestion pricing has appeared to have such beneficial impacts over just three months is a reason to be excited. Under a federal administration antagonistic to green technology and public systems, states and local governments should be taking the mantle of implementing bold climate and transportation projects.

As someone who has spent most of my life in the New York Metropolitan Area prior to moving to DC (where I am a Metrorail evangelist), it’s been invigorating to see the effort put behind this program to improve the public transit system. My family still lives in the same commuter town I grew up in where you can get to New York City by bus in under an hour, which is a boon considering the time and money saved on parking. It’s just anecdotal evidence, but I was heartened to hear my parents telling me that they’re now opting to use the bus and subway over driving into Manhattan when they can.

The key word in “public good” is public– you need buy-in from residents to make any municipal program a success. Given that 85% of daily commuters enter the central business district through public transit, investment in the modes of transportation millions of people rely upon everyday is crucial. More resilient, reliable, and well-funded subway, train, and bus systems are possible, and New York is helping lead the way forward.